State Street in front of Michigan Union, 1947

University of Michigan News and Information Services Photographs, Bentley Historical Library

University of Michigan Library Digital Collections

© Regents of the University of Michigan

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Students crossing State Street in front of the Michigan Union on the Ann Arbor campus, 1947

- Dec. 2024

IHP Teaching Fund course examines language and policy at UM-Flint

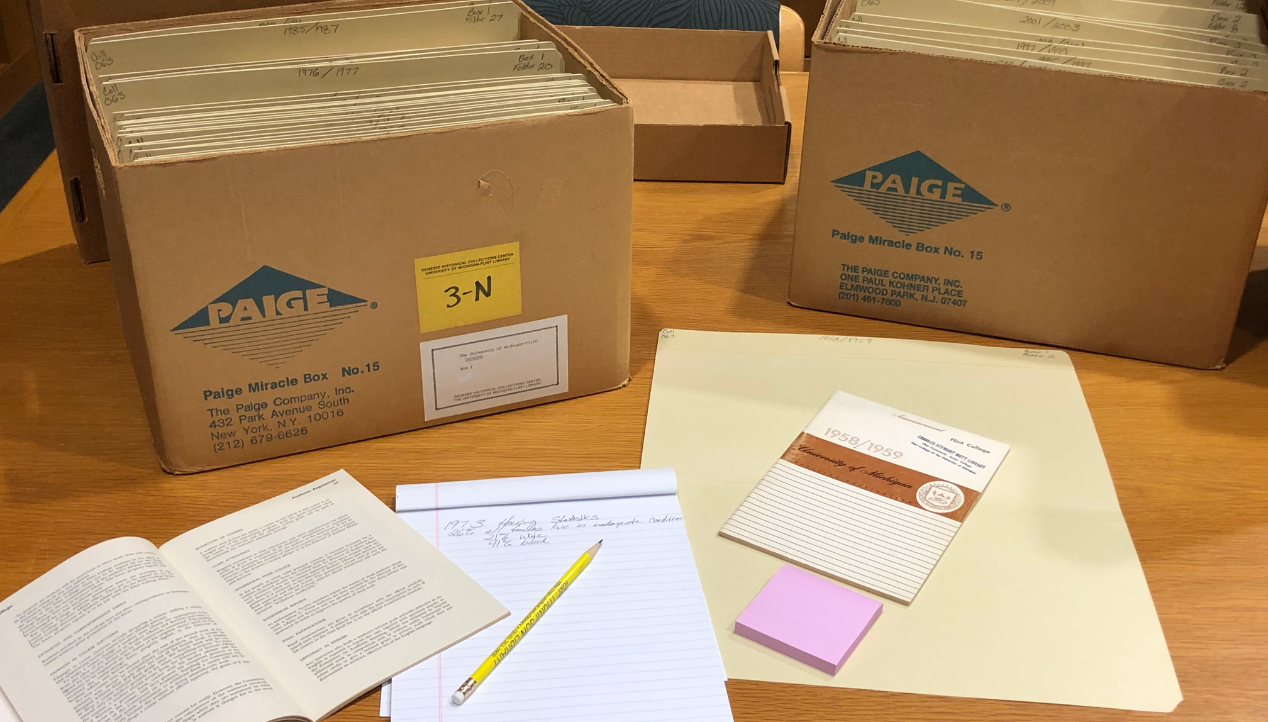

diverImage: Archival boxes with UM-Flint course catalogs at the Genesee Historical Collections Center on the Flint campus, November 14, 2024. Courtesy of Richard A. Bachmann.

Through in-depth research in a forensic linguistics class this fall, three undergraduate students at the University of Michigan-Flint made a compelling argument to the Department of Language and Communication to remove a policy from the course catalog that set up unjust standards. The course, Linguistics 231: Language and Law, is a new course developed and taught by Emily Feuerherm, Associate Professor of Linguistics at UM-Flint, with the support of an IHP Teaching Fund Course Development Grant.

This fall Alyssa Lovett, Chris Hartman, and Elsa Butterfield have been studying the relationship between language, policies, and their outcomes in Dr. Feuerherm’s course. They conducted original archival research related to diversity, equity, and inclusion policies and practices at UM-Flint and asked how they have shifted since the founding of the university. The three students have been particularly interested in investigating how institutional policies and practices related to DEI have shaped the educational experience of multilingual speakers on campus.

A few weeks into the semester, a recurring language policy caught the students’ attention while they were researching UM-Flint course catalogs from the past 68 years at the Genesee Historical Collections Center (GHCC), part of UM-Flint’s Frances Willson Thompson Library. The policy outlines a series of actions that any instructor at UM-Flint can pursue when they find a student’s writing “seriously deficient in standard written English.” Initially, instructors can refer the case to the Director of the Writing Center, and then “the student may be given additional work in composition with or without credit.” Lastly, the instructor is given the power to “refuse credit or give a reduced grade for written work which does not demonstrate accurate, effective use of standard English.”

From their comprehensive archival research at the GHCC, the students learned that the “Deficiency in English” policy entered UM-Flint’s course catalog in 1956 when the university was founded. Only slight alterations were made when Marian E. Wright Writing Center was established in 1971 on the Flint campus. The students were struck when they realized that, almost seventy years later, the same policy is in the school’s current course catalog, now available online. In fact, they had used that same online catalog to sign up for Dr. Feuerherm’s class.

Chris Hartman, Alyssa Lovett, Dr. Emily Feuerherm, and Elsa Butterfield (from left to right) share their research with students at UM-Flint’s Intercultural Center, December 4, 2024. Courtesy of Richard A. Bachmann.

The students and Dr. Feuerherm found the “Deficiency in English” policy problematic for several reasons. When viewed through the lens of linguistic theories of language, Dr. Feuerherm explains, “the ‘Deficiency in English’ policy implies a subordination of varieties of English which do not fit into a mainstream, academic, or standardized variety.” In her course, students learned that language varieties are emblematic of identities connected to race, ethnicity, homeland, or other social allegiances and that, from a linguistic point of view, all varieties of a language are fully grammatical linguistic systems with their own internal logics and structures. “That structure may differ from the preferred academic variety,” Dr. Feuerherm emphasizes, “but elevating one variety of English over others is a form of discrimination–particularly when punitive rather than supportive action is the suggested recourse.” To Dr. Feuerherm and her students, a policy that says a student could be denied credit for a course because of their language variety signals that some students’ language varieties and, by extension, their identities are less valued than those of other students. Such a policy seemed out of alignment with UM-Flint’s student-centered focus and its inclusion of diverse students and scholars. Even though they found no evidence that the policy had been utilized recently, it was still a functional policy and thus enforceable, both now and in the future.

Putting the IHP’s main objectives to research, engage, and repair, into action, the students considered the advantages and disadvantages that the “Deficiency in English” policy could have for current and future students at UM-Flint. Eventually, they came to the conclusion that it should be changed. In conversation with Dr. Feuerherm, each student drafted an alternative version of the policy. Their versions used language that provided more constructive pathways for students and instructors to pursue and avoided recommending disciplinary or punitive actions. One version, for instance, states that “students who may need extra support in their written English performance may be recommended and required by any instructor to consult the academic services provided by the University …”

After consulting with Dr. Jacob Blumner, Professor of English and the current director of the Wright Writing Center, the students started to question if even a revised “Deficiency in English” policy was still necessary. Dr. Blumner told them that the policy was not actively being used or pointed to by faculty or students and hadn’t been for some time. In fact, he didn’t even know of the policy’s existence, as it had never been referenced during his tenure as Writing Center Director. Dr. Blumner agreed that getting rid of it entirely was the best course of action.

After gathering their evidence, the students brought their concerns about the policy to the Department of Language and Communication. Their recommendations for an alternative version sparked robust discussions among the department’s faculty about the language used in the current policy and its potential implications for students across campus. In the end, the faculty decided to vote on whether the policy should be removed from future course catalogs, beginning next year. A majority voted in favor of the motion. The suggested change was circulated through the typical channels for catalog changes and was supported by the Provost’s Office. When students enroll for Fall 2025 courses at UM-Flint, they won’t do so through a catalog that includes that policy.

Alyssa, Chris, and Elsa’s efforts to avert the potential harms of UM-Flint’s “Deficiency in English” policy exemplifies the IHP’s main objectives. The IHP aims for the original historical research supported by the project on all three U-M campuses and at Michigan Medicine to spark crucial conversations about inclusion and exclusion as well as equity and justice. These conversations are meant to bring together students, faculty, staff, and community partners who are eager to create not only a more inclusive history of the university, but also a more inclusive present and future.

As in the past, students like Alyssa, Chris, and Elsa continue to play a central role in changing our university community in positive ways, creating a space where everyone can flourish. Words and policies are among the means that change makers use to bring about change. But they require action to become operational.

By Richard A. Bachmann, IHP Research Associate

This article was developed in consultation with the students and instructor of Linguistics 231, as well as the IHP team.